THE WORLD OF MILITARY UNIFORMS

1660-1914

THE AUSTRIAN ARMY 1700-1867

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Rudolf Ottenfeld, born in 1856 was a student at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna under Karl Wurzinger and Leopold Carl Müller. He lived in Munich in 1883–93 and Vienna in 1893–1900. For the Sixth International Art Exhibition in Munich in 1892, he was selected as a juror. Ottenfeld's illustrations in a history of the Austrian army between 1700 and 1867 in 1895, which became a standard reference work on uniforms in the period.

He was a founding member of the Vienna Secession, an art movement formed in 1897 by a group of Austrian artists who had resigned from the Association of Austrian Artists. He sat on the Secession's working committee and the title page of the fourth issue of Ver Sacrum, the official journal of the Secession, was designed by Ottenfeld. After the death of Julius Mařák in 1899, Ottenfeld was appointed to the Academy of Fine Arts, Prague. Among his students in Prague was the painter and art restorer Zdeněk Glückselig. He spent thirteen years there as a professor, until his death in 1913.

By Rudolf Otto von Ottenfeld

Page 1

PART I

THE AUSTRIAN ARMY OF THE 18TH CENTURY

From the book by Bruce Bassett-Powell published by Uniformology in 2007

The Thirty Years War ended with no real winner and devastation on a scale not seen again for over two hundred years. Ger many was laid waste leaving many of its kingdoms, principalities, electorates and other petty states impoverished while Austria, or more aptly the Hapsburg Empire, emerged as strong as ever.

Within twenty years of the Treaty of Westphalia, its armies were on the march again. They fought in all the wars of the late 17th century; the Dutch Wars and the War of the League of Augsberg (or the war of the Grand Alliance) 1688-1697. The War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) saw the Austrian forces under their great general Eugene of Savoy pitted against France, Bavaria, and Spain. Alongside him was the Duke of Marl borough and his British Army with their Dutch and Prussian allies. In1704 they combined to beat the Franco-Bavarians at Blenheim under Tallard, causing Bavaria to exit the war. For the next four years Eugene and the Austrian Army campaigned in Italy then united again with Marlborough in the low countries to overcome the Franco-Spanish forces at Oudenarde in 1708. In1709 defeated Marechal de Villars at the battle of Malplaquet leaving twenty thousand of their own dead upon the field.

The Treaty of Utrecht aggrandized Austria, especially in the Netherlands and Italy and made her the most powerful entity in central Europe. No sooner had this peace been negotiated that the Austrian Army (with Venice as an ally) was fighting again, this time with Turkey, in the Balkan states. At the end of this war, by the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718 the remaining parts of Hungary held by the Turks passed to the Hapsburgs. There were two more wars with the ever-weakening Turkey in 1737 and 1787, with Russia as an ally.

In 1733, Austria allied with Russia in the War of Polish Succession and mainly campaigned in Italy where they defeated the Franco-Spanish at the Battle of San Pietro in 1734 then lost to them in the Battle of Luzzara three months later. Defeat at the hands of the Spanish in the south at Bitonto resulted in the loss of the Hapsburg lands in Naples and Sicily. At the conclusion of the war in 1738 (Treaty of Vienna) Austria gained Parma and Tuscany.

In 1740, Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor, died leaving no male heir. His eldest daughter Maria Theresa, had been granted accession to his Austrian and Hungarian thrones and lands under the will of his prede cessor, Leopold. Although the crown of the Holy Roman Empire was not at issue, its vacancy or succession by a non-Hapsburg was a break with a long tradition. This Will, known as the Pragmatic Sanction, was contested by a number of nations, including France, Prussia, Bavaria and Saxony who had previously agreed to it. The same year, Frederick the Great of Prussia invaded Austrian Silesia beginning the 1st SilesianWar (1740-1744) that became known as the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), placing Austria, Great Britain, the Netherlands and Russia against the alliance of Prussia, France, Bavaria, Spain and Sweden, later joined by Sardinia and Naples.

Austrian Armies along with their Hungarian troops fought in all theaters from Silesia to Italy and from the Low Countries to Bohemia. Frederick and his magnificent army bested them at almost every turn in the Silesian campaign with the battles of Mollwitz and Chotusitz being the most notable of Prussian victories. In 1743, Frederick with drew from the war. Charles VII of Bavaria was crowned Holy Roman Emperor, but he died two years later after defeat at the hands of Austria. In 1744 Frederick led Prus sia back into the war (the 2nd SilesianWar) confirming superiority over Austria at the battle of Hohenfriedburg in 1745 where the armies of Austria under Charles of Lorraine were destroyed.

We do not have space to recount the labyrinthine twists and turns of the War of Austrian Succession, but despite their losses, the Hapsburg armies survived intact. Al though Prussia retained Silesia, Maria Theresa, whose husband, Francis I had been elected as Holy Roman Emperor in 1745 was accepted as the sovereign of Austria, Hungary and Bohemia. Maria Theresa, in her long reign as Queen had a great impact on the Hapsburg Empire and her reforms reached into every institution. Not least of these insti tutions was the Army, which became themost powerful in Europe.

Its next test would be the Seven YearsWar (1756-1763). In many ways a continuation of the War of Austrian Succession. It began in 1756 with Frederick the Great invading Saxony. Although he des troyed and captured the Saxon Army, his move into Bohemia was checked in early 1757 at Kolin by a rejuvenated Hapsburg Army led byMarshal Leopold J. von Daun who demonstrated the superiority of his artillery. 1757 brought other countries into the war. the Brit ish, along with Hanover, sided with Prussia after a complicated round of diplomacy which saw France separated from her erstwhile ally, and aligned with Austria, Rus sia, Sweden and most of the German electorates and petty states.

Surprised by the Austrian success at Kolin, Frederick intensified his efforts and at Rossbach on November 4th he defeated a French Army along with their Imperial allies. Moving swiftly east to counter Austrian moves in Silesia, he retook Breslau and on 5th December, 1757, in his most brilliant battle he defeated the Austrian army under Charles of Lorraine at Leuthen. This was the high point of Frederick's fortunes, for despite a victory at Zomdorf against the Russians in August 1758, he was defeated by Daun again with a combined Russian / Austrian force at Kunersdorf a year later. Although he was able to outmaneuver the Hapsburg and Russian armies on several occasions during the next few years his army was gradually weakened by the constant pressure from the numerically superior forces arrayed against him. By the end of the war in 1763 Prussia was impoverished.

With the Treaty of Paris that ended the war Maria Theresa and her army emerged as strong as ever. Though she never regained Silesia, her vast Empire was secure from Prussian aggression for the rest of her reign. The true winner of the Seven Years War was Britain who had waged war against France in India, North America and on the high seas and prevailed everywhere leaving her with the mightiest Empire in the world. Apart from the constant warfare on her borders with the Turks, Austria was at peace until the death of Maria Theresa. Her army became legendary and by the end of her reign it had acquired the identity that would define it until 1918. It was one of the largest and most diverse armies in the world. In its ranks, apart from the German speaking Austrians were Hungarians, Bohemians, Moravians, Italians, Poles, Slovenes, Slovakians, Romanians, Ruthenians, and Croats. From its border territories came colorful irregular Pandour and border units from Bosnia and Serbia. It was one of the first countries to field the le gendary Hussar regiments from Hungary.

At the death of Maria Theresa the Hapsburg Armies consisted of 59 infantry regiments(ll of which were Hungarian), 7 Border Infantry Regiments, 12 Cuirassier Regiments, 13 Carabiniers & Dragoons Regiments, and 15 Hussar Regiments The artillery was considered to be the finest in Europe and there were technical corps of engineers, sappers, pioneers, pontonniers and miners. Despite not often being victorious, the Hapsburg armies had the depth to wear its enemies down. This was never more so than during the twenty-six years of warfare with revolutionary, later Napoleonic France. Even though defeated time after time, the Austrian 'whitecoats' would be back to face their enemies stronger than before until they were the last ones standing.

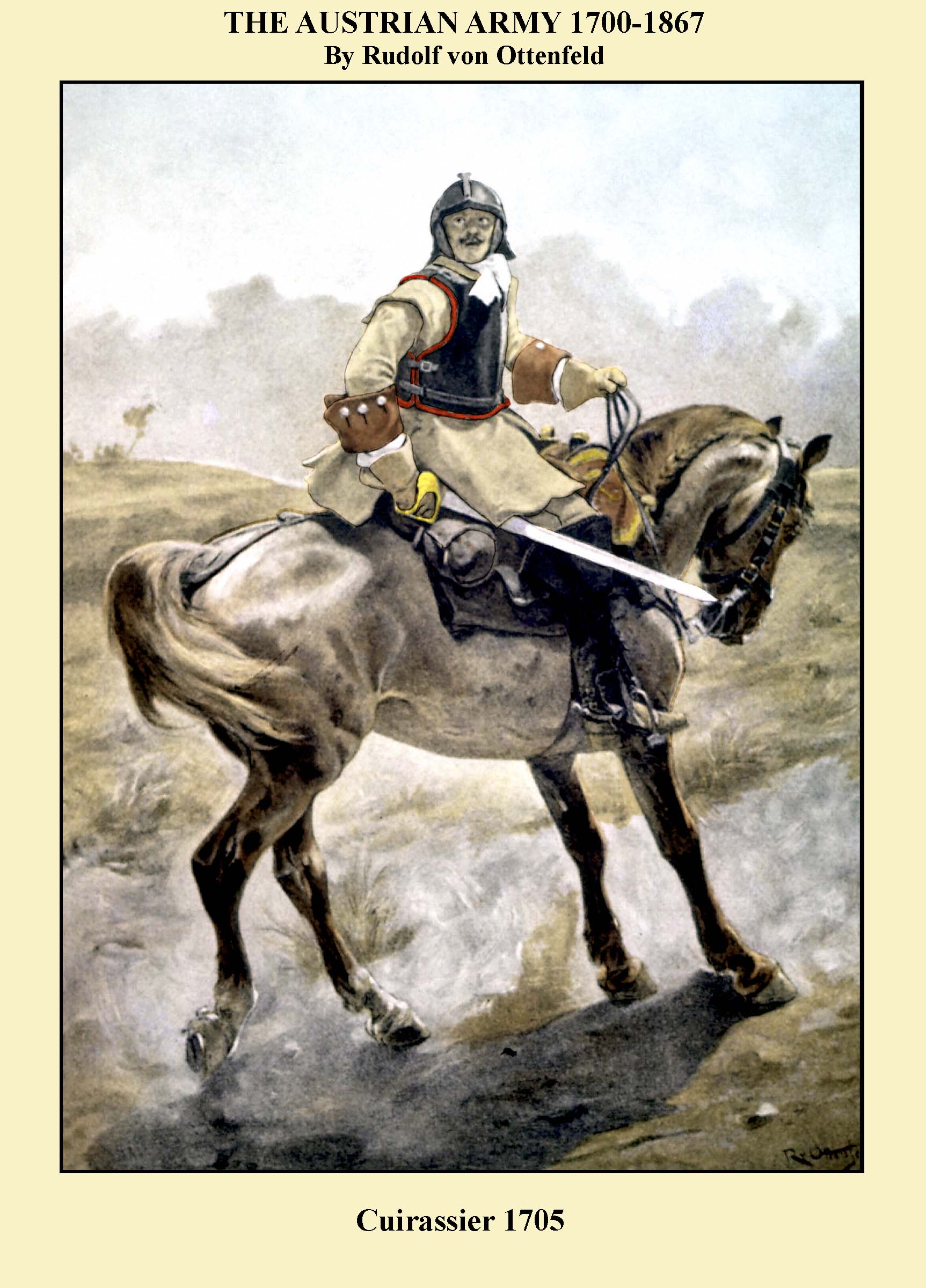

Cuirassiers 1700

The uniforms worn by the heavy cavalry of Austria were little changed in appearance from the Thirty Years War. The heavy leather jerkin, cuirass and large top boots were typical of this arm in most nations. The lobster pot helmet had, however disappeared from most armies by this time

and by the end of the War of Spanish Succession, Austrian Cuirassiers were wearing the tricorne hat with an iron skull protector in the crown. The large turn back cuffs were mostly red or dark red in the fifteen regiments existing at the time although two had light blue.

Infantry 1690-1710

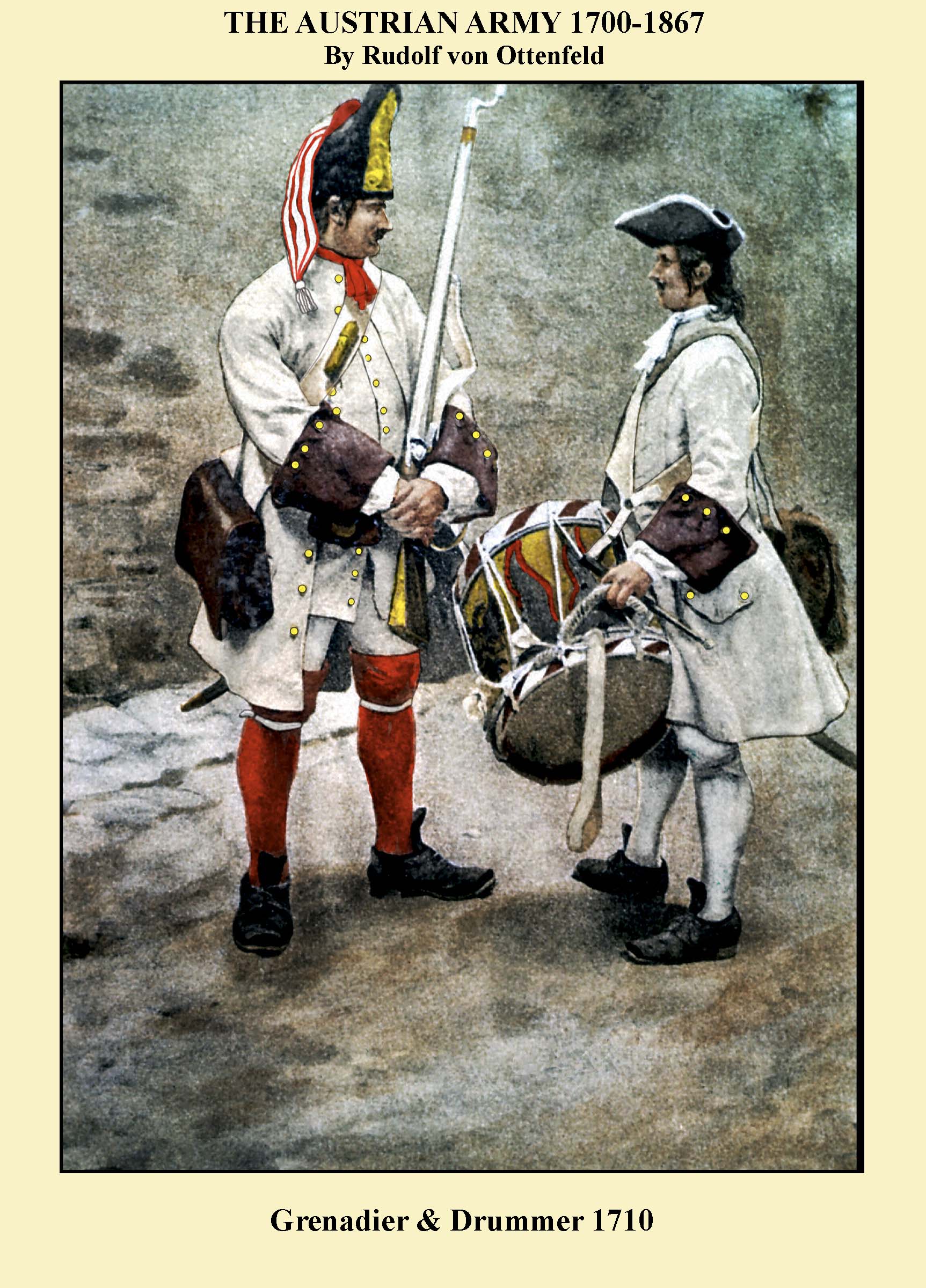

This plate shows a grenadier and drummer in about 1710. The coats of the Austrian infantrymen in the late 1690s were of various colors including dark green, blue and red. The predominant color was grey, later described as ‘pearl’ grey. By the middle of the first decade of the eighteenth century, nearly all regiments were in grey, but officers were still choosing to wear coats in ‘reverse’ colors. The grenadier shown is typical. The fur cap had by now evolved into the form that would be familiar for the rest of the century. The front was almost entirely covered by the brass plate. This plate often varied between regiments in size and shape and a number of units still wore cloth fronted caps with plain or brass fronts. The bag was red for most regiments with the white trim and tassel and the stockings were red or grey. The drummer has a rather plain uniform which may be for use in the field. Many drummers still wore reverse colors with coats adorned in accordance with the colonel’s wishes.

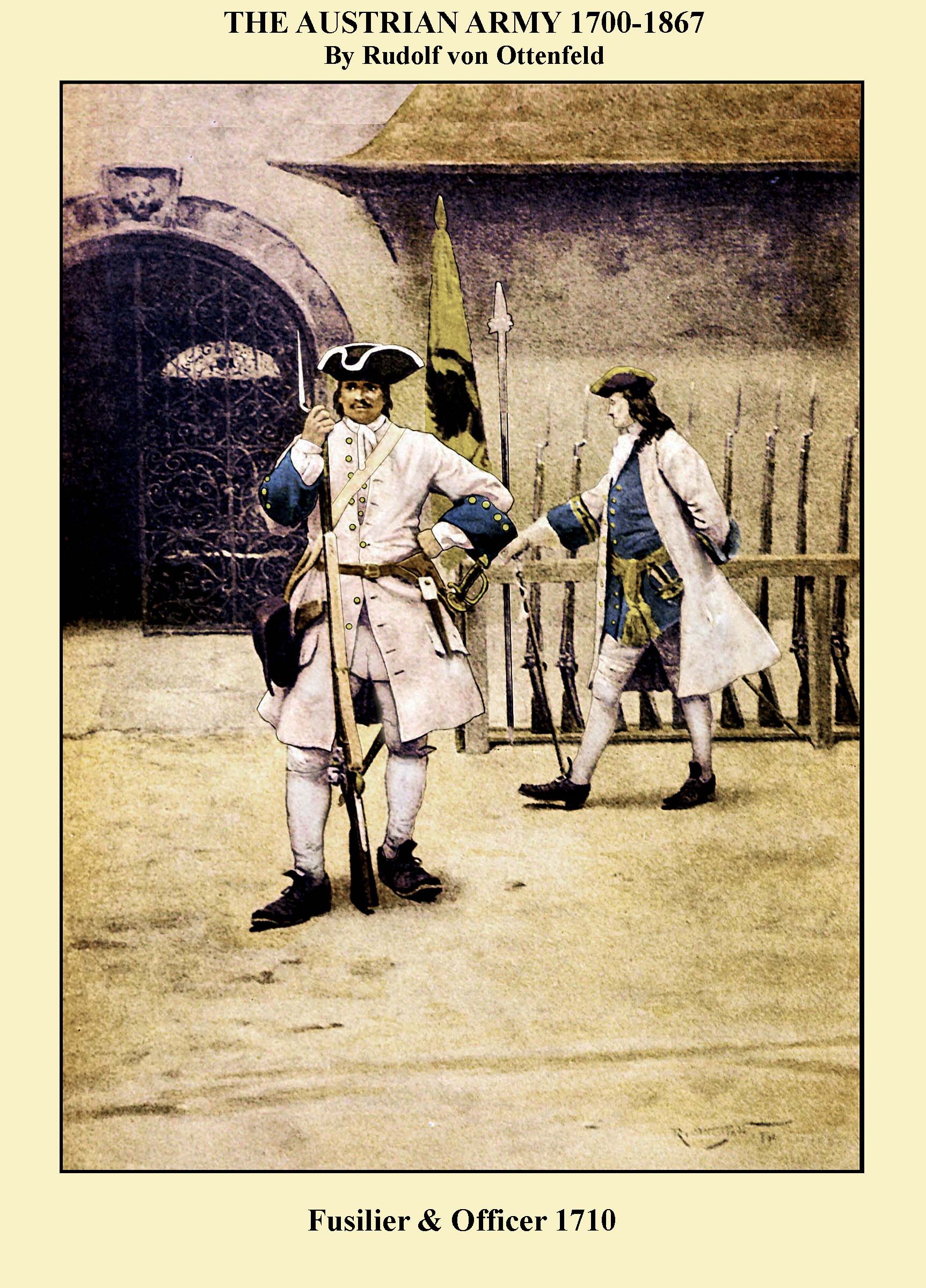

Infantry 1710

By the end of the War of Spanish succession, the Austrian Infantryman was, for the most part, uniformly dressed. The pearl grey coat was becoming white and many regiments at this time were actually dressed in white. Hats were now trimmed in white tape and a cockade on the left would be soon introduced. The officers were also wearing coats of the same color as the men, but generally worn open with a waistcoat in facing color. The gold and black sash, which would be a feature of the Austrian officer until 1918 was now being worn around the waist.

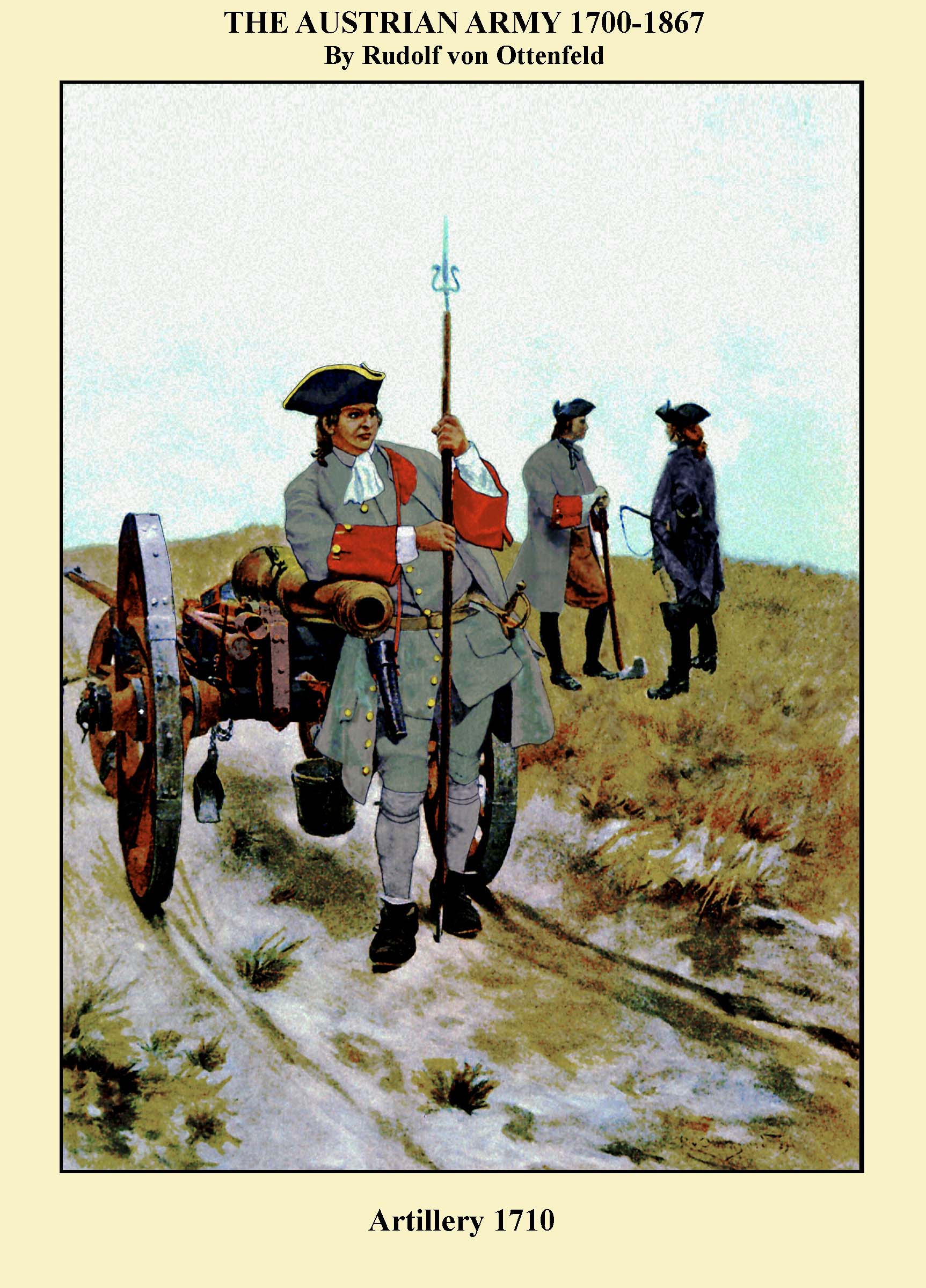

Artillery 1710

The artillery arm of the Austrian Army was one of the most efficient in Europe. Artillerymen everywhere were treated as specialists or artisans and generally received better pay and conditions. The gunner shown in the foreground is wearing a coat of better materials that that of the common soldier. The color of the coat was officially described as ‘wolf’ grey which was a darker shade than that of the infantry. Instead of becoming white, it would evolve into brown. The two figures in the background show a matross, or workman whose job was to help make the gun emplacement, and a driver who is likely to have worn civilian clothes.

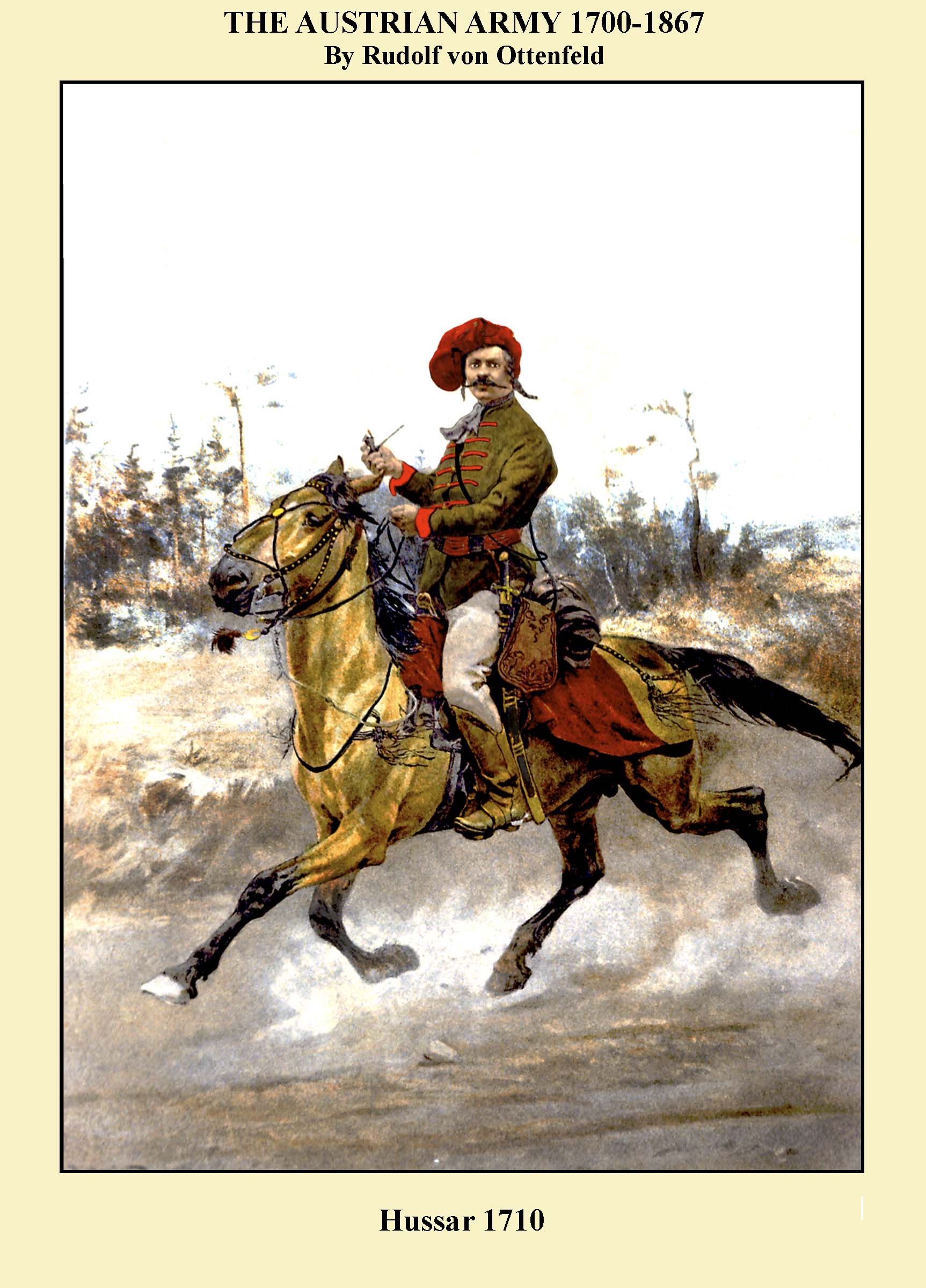

Hussars 1710 - 1720

Because of the special relationship between Austria and Hungary, one would assume that the national horseman of the latter country would first be organised by the former. This was not so. Hungarian horsemen were mercenaries first and foremost. The famous Bercheny Hussars raised to fight the Turks in 1686, would become part of the French Royal Army. The Locatelli regiment joined Maximilian of Bavaria’s army before the turn of the century. The Nadasdy regiment, raised in 1688 to fight for Austria was soon disbanded, although when raised again in 1734, it would recognize that as the date of its formation. The Hussars that fought for Austria in the War of Spanish Succession were formed into squadrons or bands of 200 men or more and wore no regular uniform although green, red and blue predominated. Despite this, the features of dress that would become the hallmark of hussars everywhere were evident. The fur cap with colored bag, the short coat or dolman with colored loops across the chest, the fur lined cloak thrown over the shoulder and the tight pants were common to most of these cavalrymen.

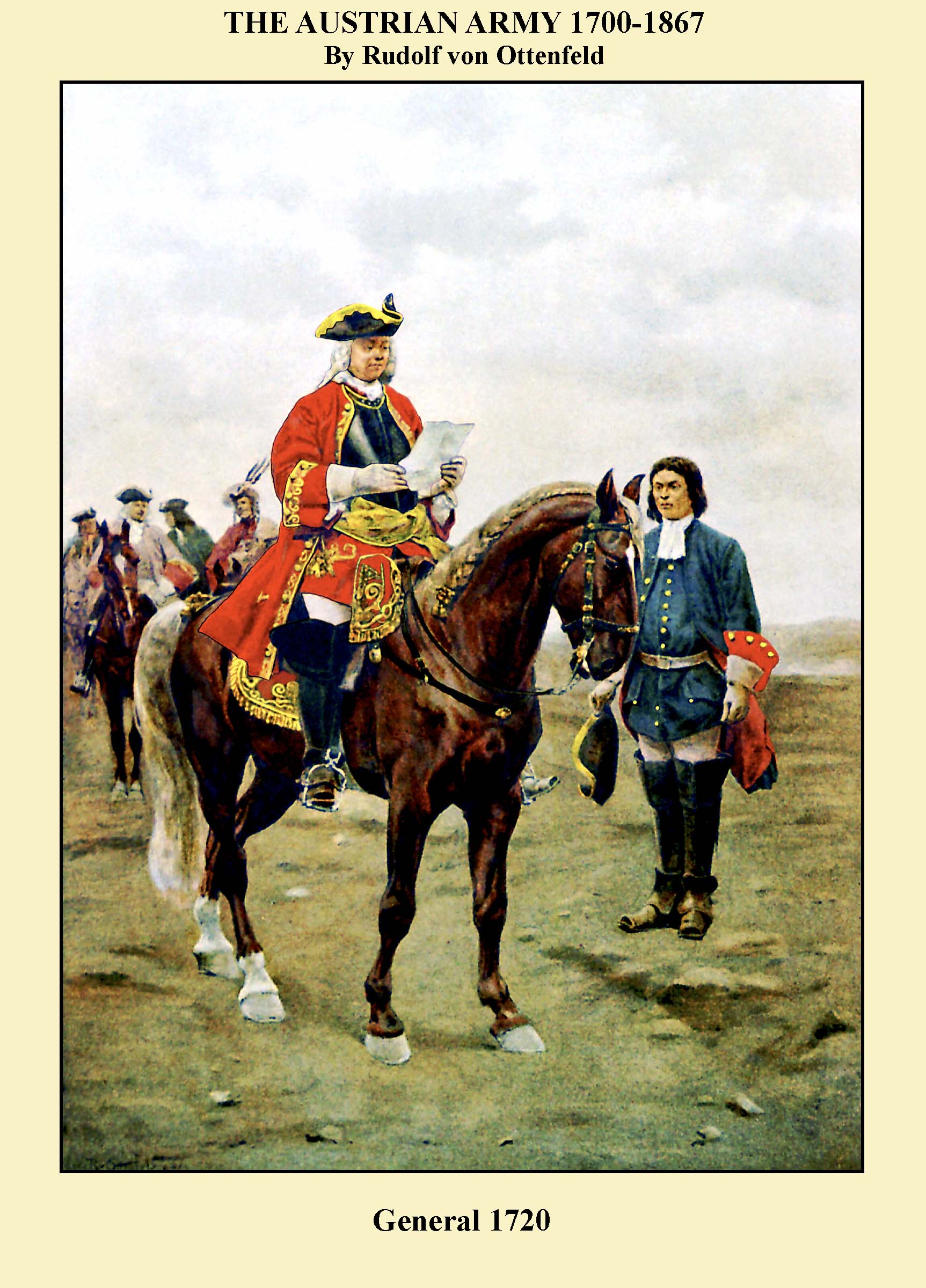

General Officers 1720-1745

There was no regulation uniform for General Officers until 1751, therefore it was entirely up to the individual officer as to what he wore. A coat of civilian cut, richly decorated with gold or silver lace was the most commonly worn garment. Prince Eugene of Savoy is often shown wearing a fairly plain brown coat, although the amount of gold lace seems to vary between artists. In the years following the War of Spanish Succession, it became common for Generals to wear the coat of their regiment, albeit lavishly laced. The General in plate is likely a cavalry officer, perhaps of dragoons. The wearing of a cuirass was common among Austrian senior officers. Eugene is often depicted wearing one over his coat although after 1715, officers wore them over the waistcoat but under the coat.

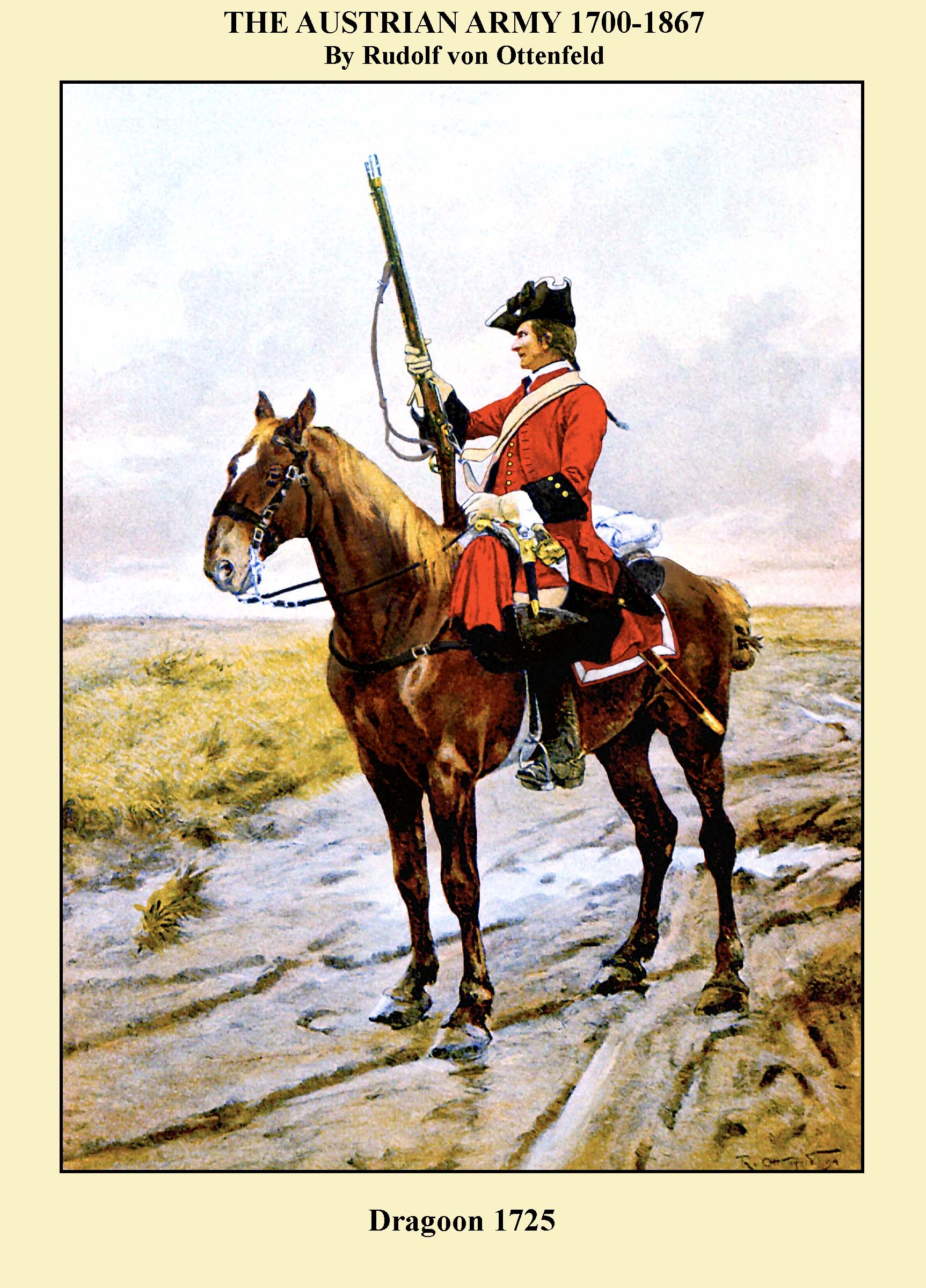

Dragoons 1725

Dragoons were originally raised to act as mounted infantry and this plate clearly shows a trooper in this classic role. In 1702 there were three regiments of dragoons for the most part dressed as infantry except for the heavy leather cavalry boots. There were three dragoon regiments in 1710 the first two wearing blue with red cuffs, the third in red with black cuffs. This plate show’s the latter Prince Eugene of Savoy’s (later the 9th) Regiment in 1725. During the wars of 1702-1714, the Dragoon arm was augmented by Spanish regiments, dressed in yellow or green with a headdress of stiff cloth with a high front, rounded at the top, of coat cloth with a wide lace edging. This headwear was adopted by various Austrian dragoon regiments after the war.

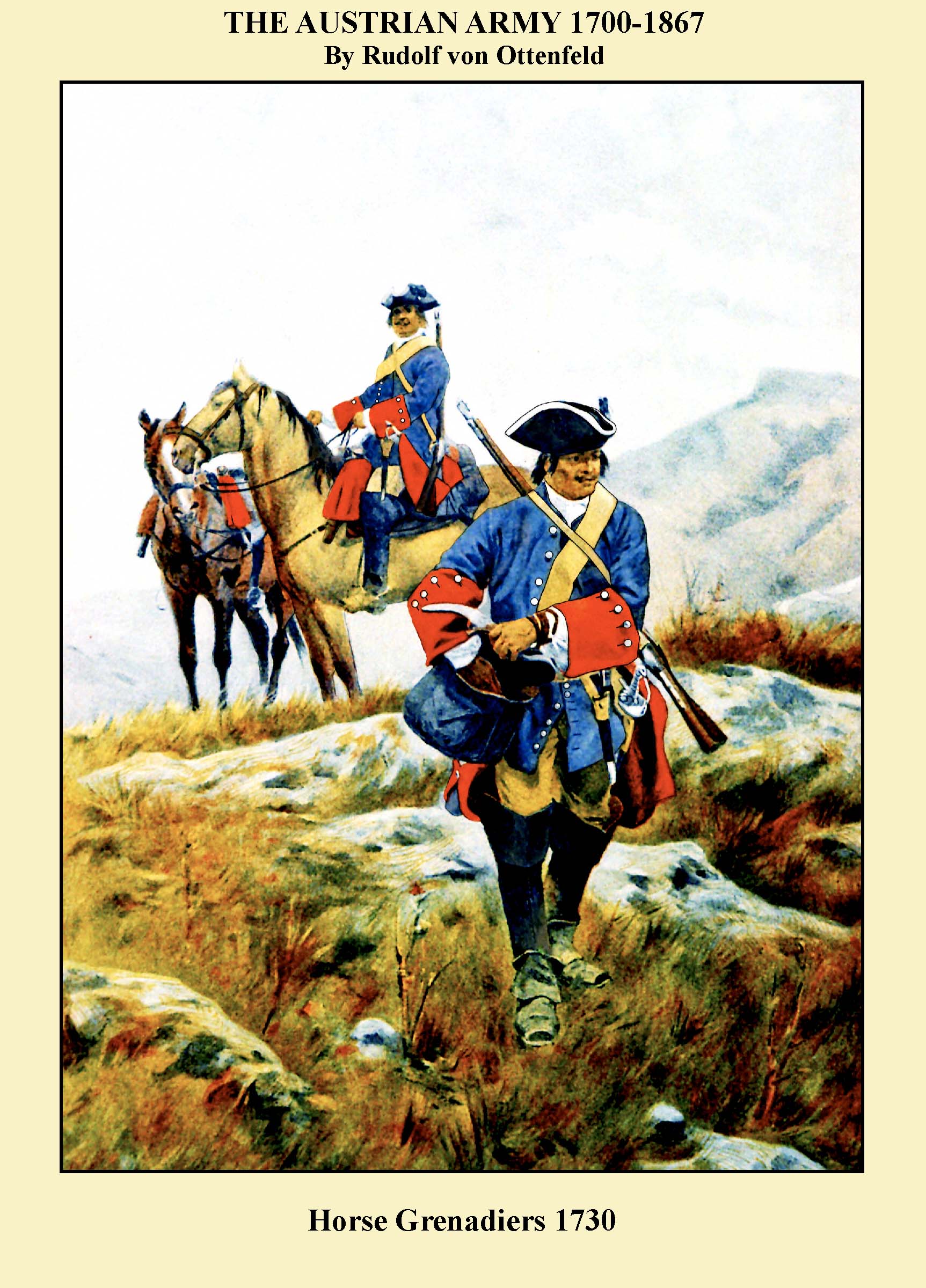

Horse Grenadiers 1730

This plate shows a horse grenadier of the senior regiment of dragoons, the Bayreuth, which became the Regt. Batthianyi (No. 7). By this time most of the Horse Grenadier squadrons had adopted a fur cap (see plate 12) like their brothers in the infantry. Many of these caps bore a brass front plate or were even made of cloth resembling a mitre cap or the high fronted cap of the Spanish dragoons. Before 1740, this regiment’s horse grenadiers had been issued with a fur cap bearing a high brass plate with rounded top adorned with a grenade upon a red ground.

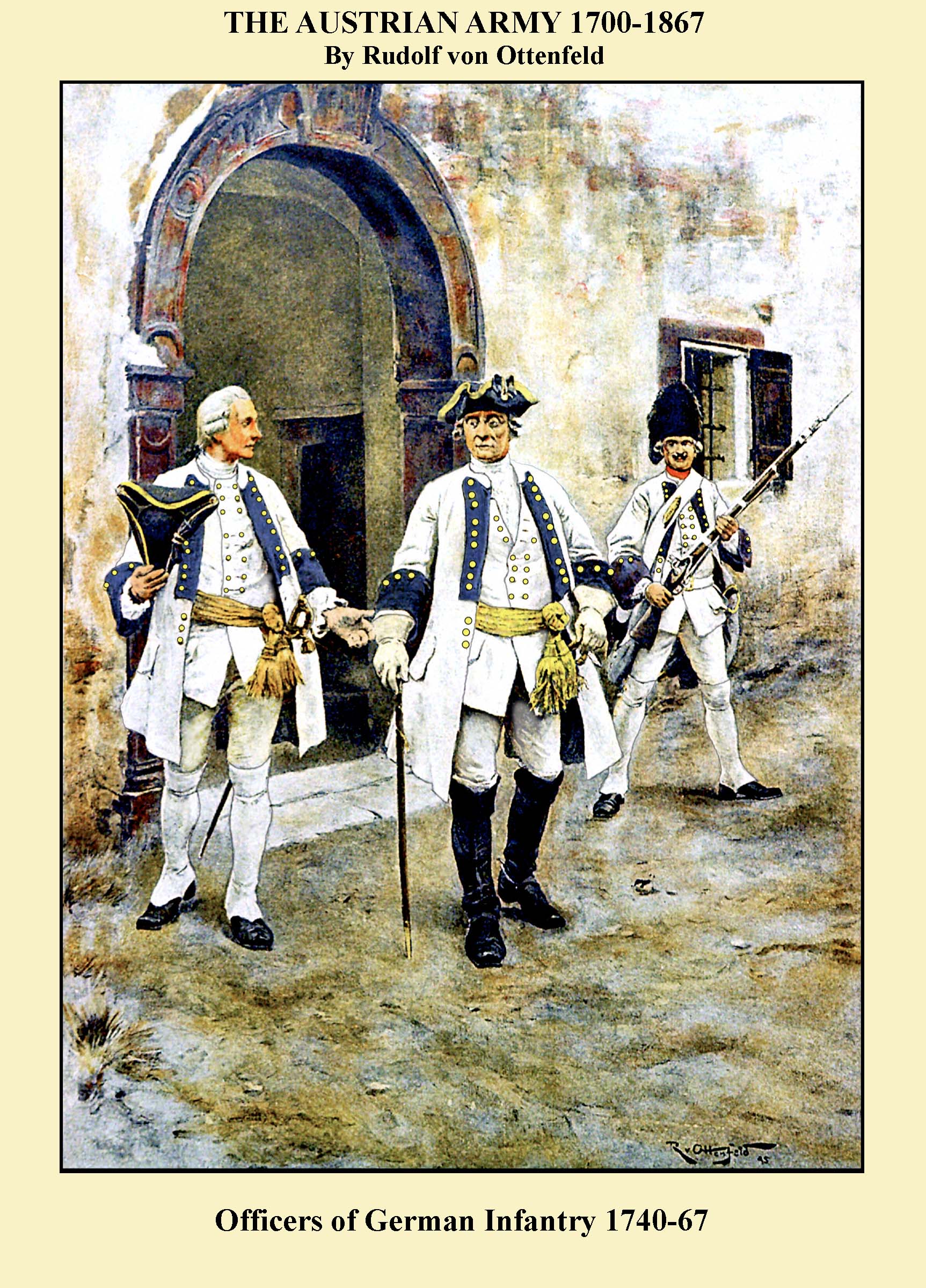

German Infantry 1740-1767

Upon the accession of Maria Theresa, the uniforms of the Austrian army became much more regulated. The infantry was now completely clothed in white coats with lapels and cuffs of facing color. The brim of the tricorne hat was edged in white tape and many regiments had colored pompoms on the left side. Gaiters were white for summer and black for winter although the former were soon reserved for parades and gala occasions. In 1755 knapsacks with cowhide flaps were issued and worn slung over the right shoulder. Officers wore the gold sash (From 1743-45 a green sash with gold thread was worn) and carried a spontoon (or partizan) for parades and canes otherwise. Grenadiers now wore the fur cap universally with the bag of facing color laced white. A number of regiments adopted brass plates.

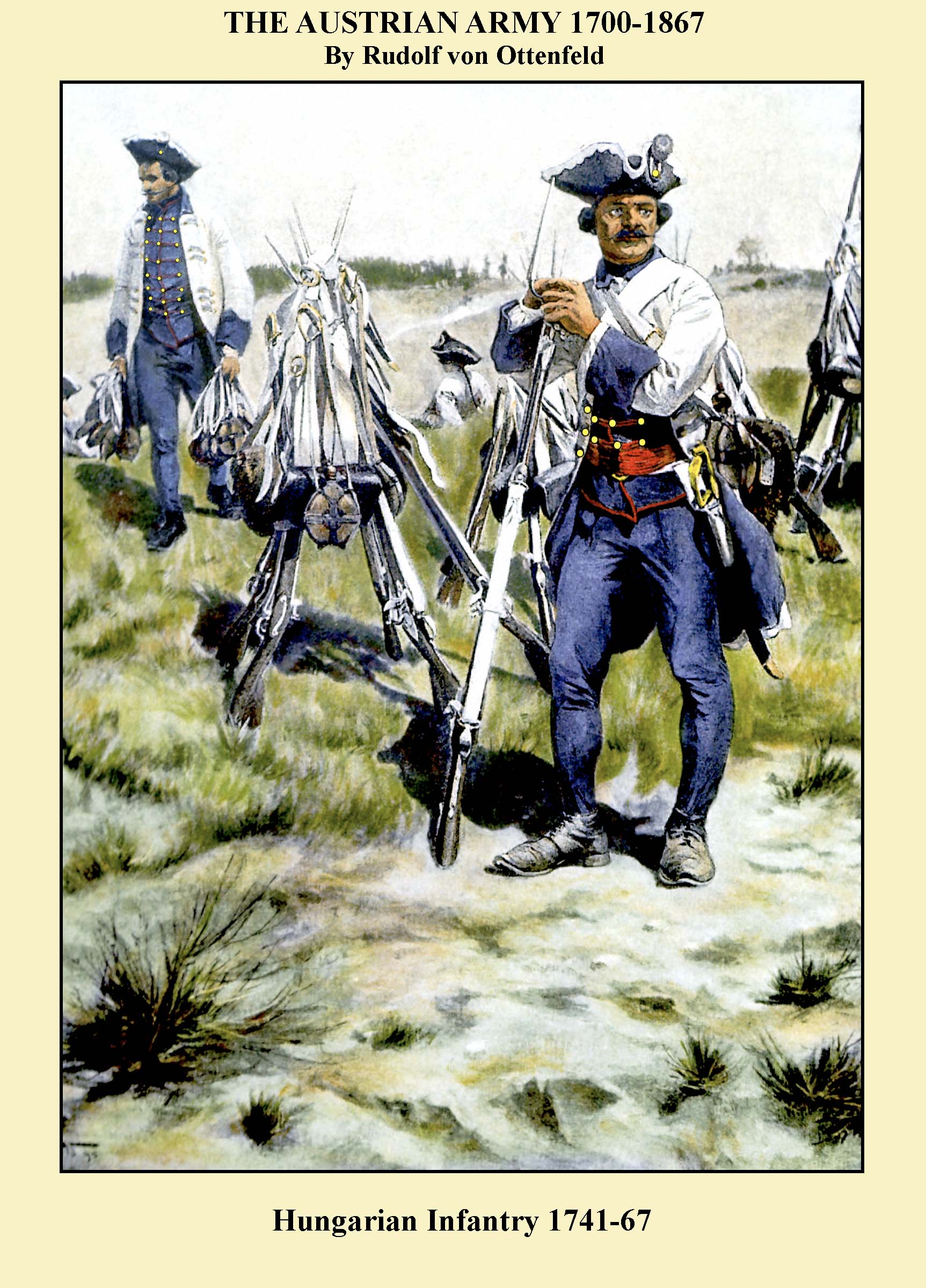

Hungarian Infantry 1741-1767

The Hungarian infantry regiments became attached to the Austrian army in 1741. There were six ‘legions’ all of whom, for the most part, wore dark blue hussar uniforms with frogged coats, colored collar and cuffs with tight blue or red trousers tucked into heavy shoes. Fur hussar caps with colored bags were worn. When these legions were formally absorbed into the line of battle as regiments they adopted a more Austrian garb including a white coat, tricorne hat and bearskin cap for grenadiers. However, they retained important national features such as the colored frogging on the coat and the tight trousers, now in light blue or red.

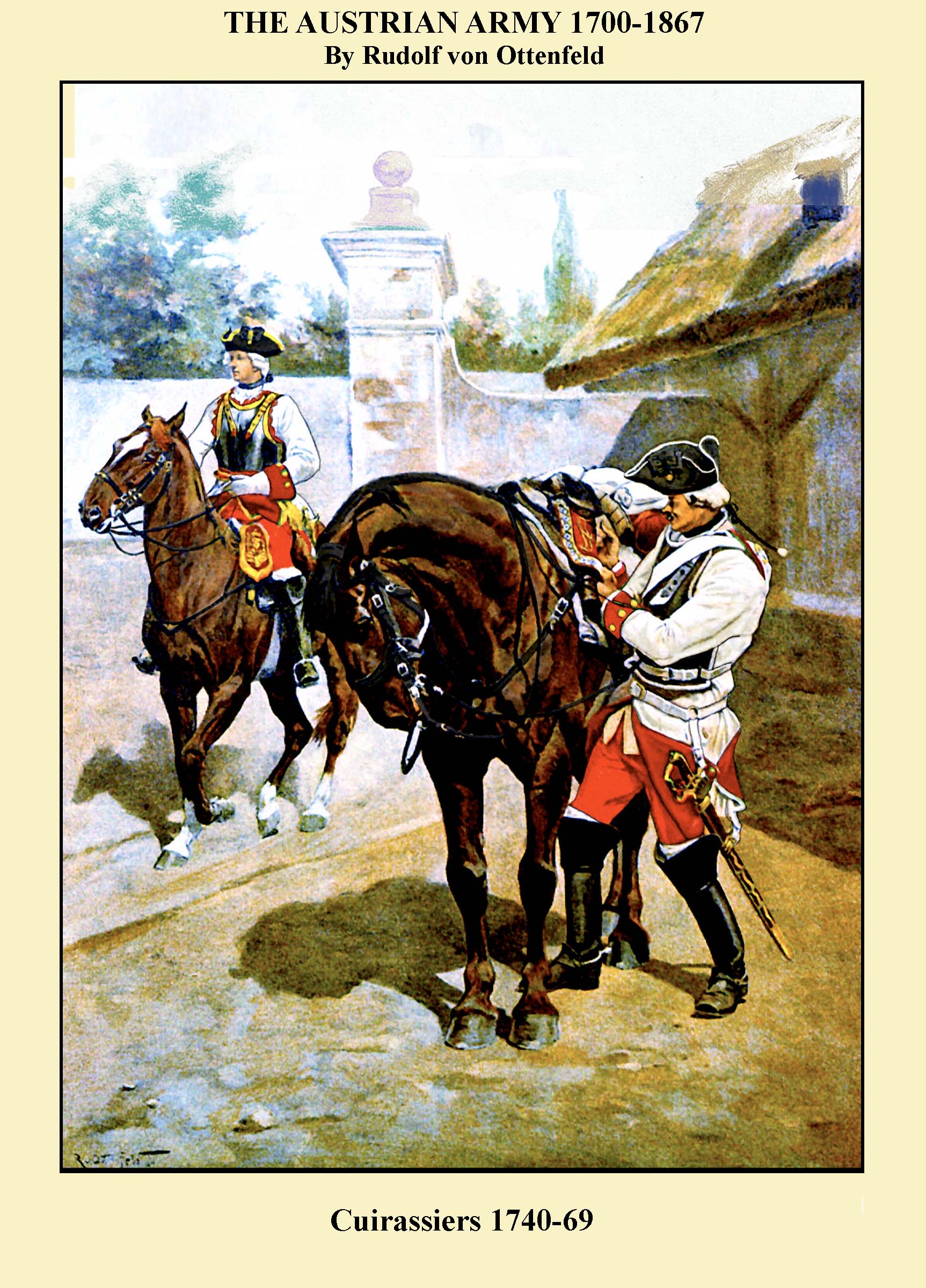

Cuirassiers 1740-1769

The white coat was now worn by cuirassier regiments throughout all with red cuffs except the Modena Regiment which wore blue. Individual regiments distinguished themselves by different button arrangements on the colored waistcoats of straw, white or red. The breeches were also either white, red or straw and each regiment had a different pattern of shoulder strap. Much of this detail was less apparent when they were mounted wearing the polished black cuirass. This uniform was worn unchanged for almost thirty years.

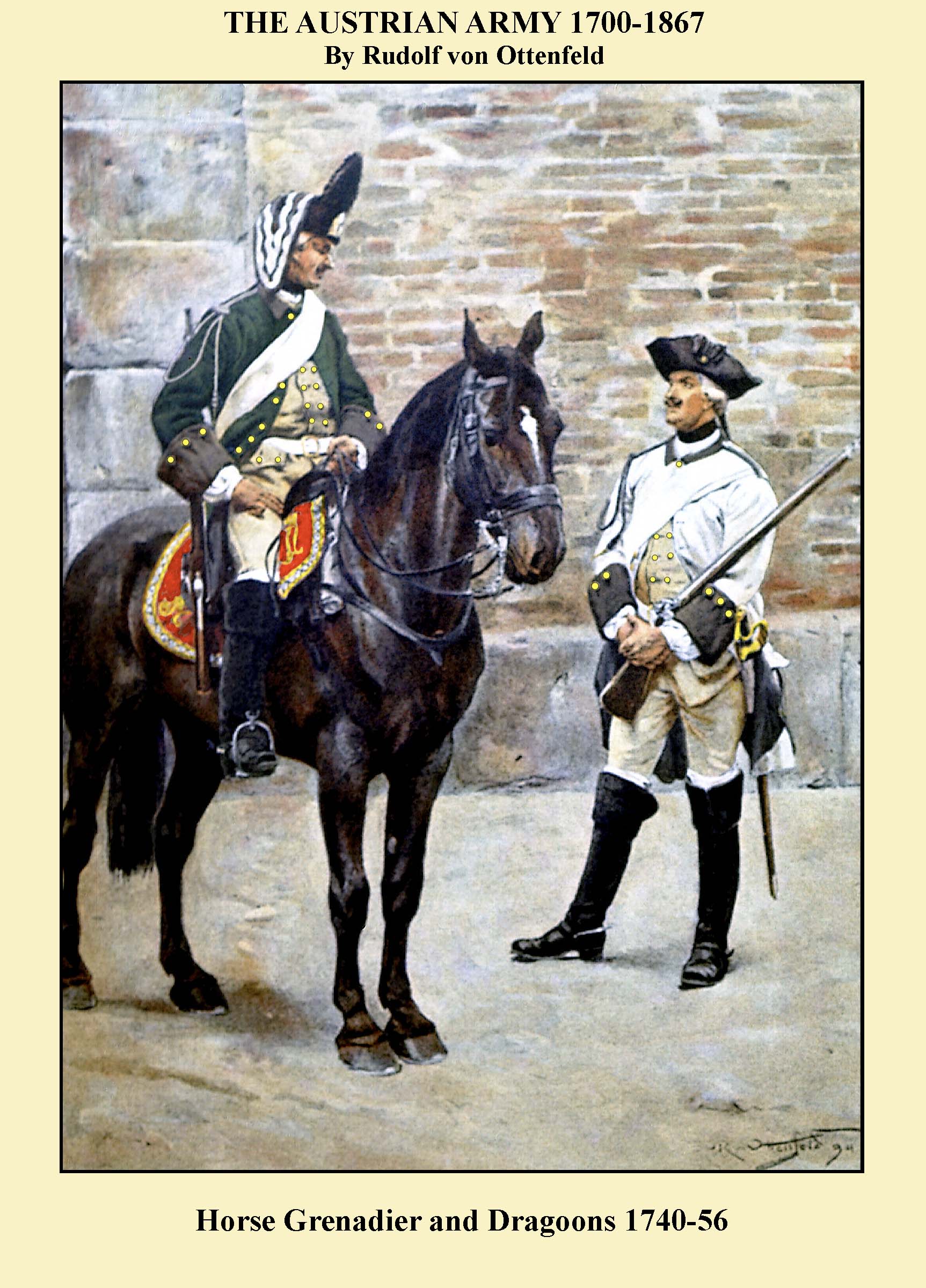

Horse Grenadiers and Dragoons 1740-1756

This is the typical dress for the dragoon branch of the period. The figures shown do not seem to apply to any particular regiment as the only white coated dragoon regiment (Althann) wore red lapels and cuffs. The horse grenadier also is in doubt as all green coated dragoons wore red facings. The uniforms of dragoons seemed to be under special scrutiny over this period as proposals for change were made in 1757 for an all blue coat that was not adopted and in 1765 new regulations were issued for red coats and new facings for all regiments. This last order was not taken up either and finally in 1767 a white coat was ordered with different colored facings. Some years before, a few dragoon regiments had been converted to Light Horse (Chevaux-Legers) and were issued with light green coats. The first of these was Lowenstein..

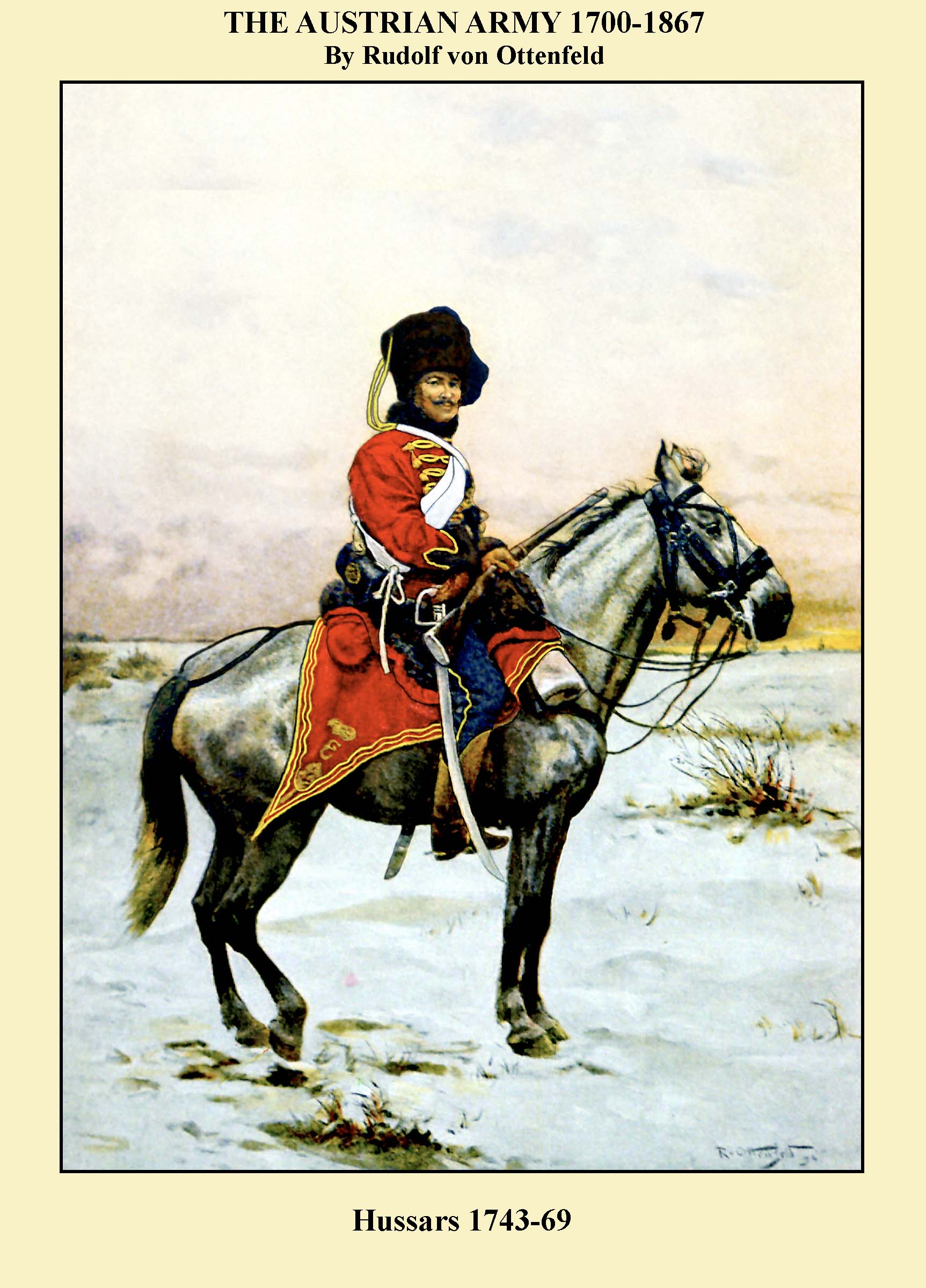

Hussars 1743-1769

This In 1743 the Hussar element of the army was expanded dramatically. All the fifteen regiments were dressed in the same highly colorful manner. The headwear was the large fur Kolpack with colored bag and the dolman and fur lined pelisse had loops of lace across the front with three rows of buttons. The breeches were tucked into short leather boots. The figure in the plate, although correctly styled is not a known regiment although the Carlstädter regiment had a similar uniform.

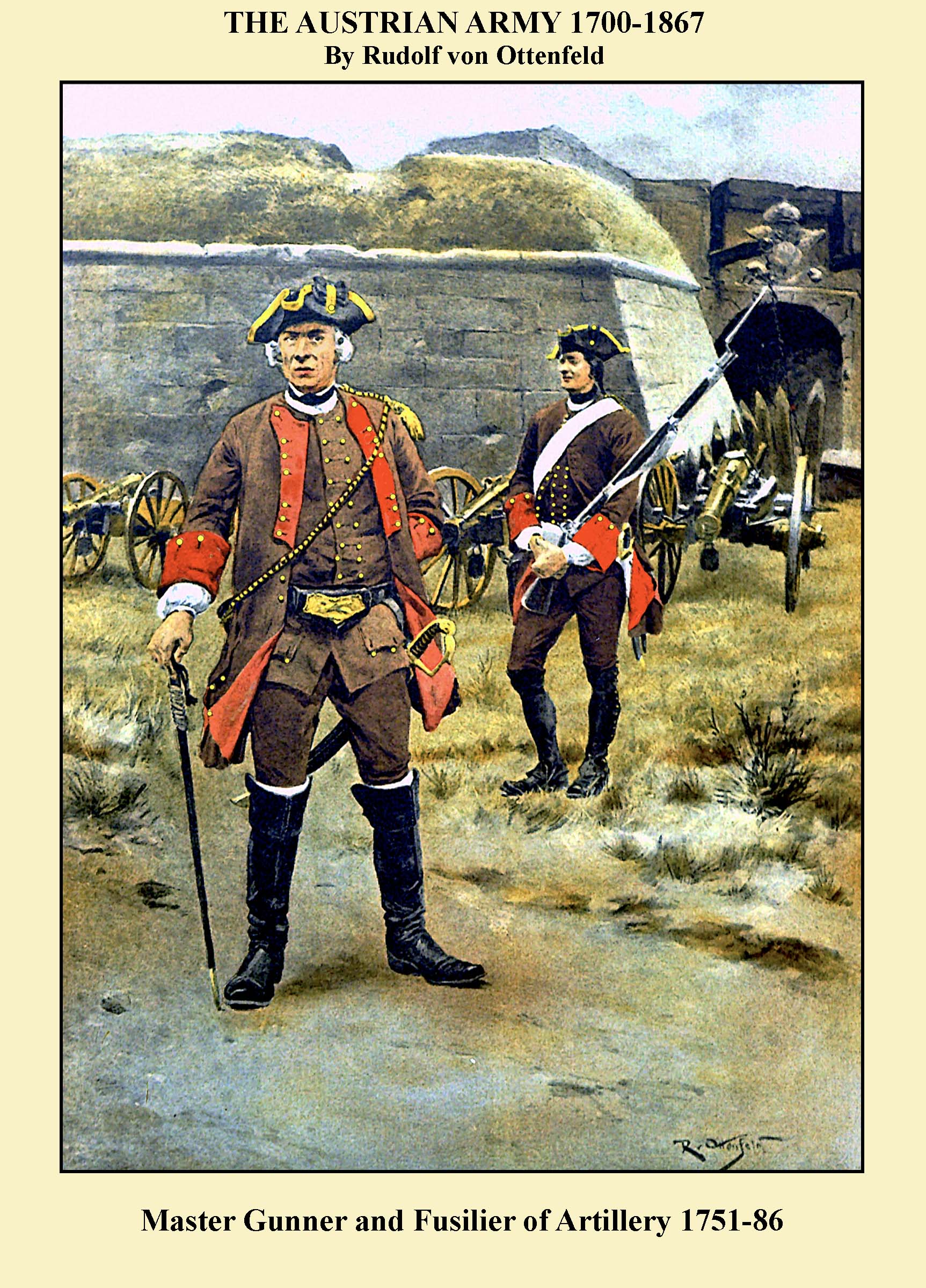

Artillery 1751-1786

This plate shows the Hapsburg artillery in the color scheme it retained for the rest of its existence until 1918. The brown coat with red cuffs were adopted in about 1739 and , for a time was much lighter in shade than it would become in later years. It was interestingly described as ‘wolf grey’ for many years after it had become brown. There were two distinctive sections of the artillery at this time; the German Artillery and the Netherlands Artillery and the former wore plain coats while the latter had red lapels. It is a Master Gunner of the Netherlands Artillery depicted in the foreground of this plate. The figure in the background is a fusilier of the German regiment. Later in Maria Theresa’s reign these uniforms became grey.

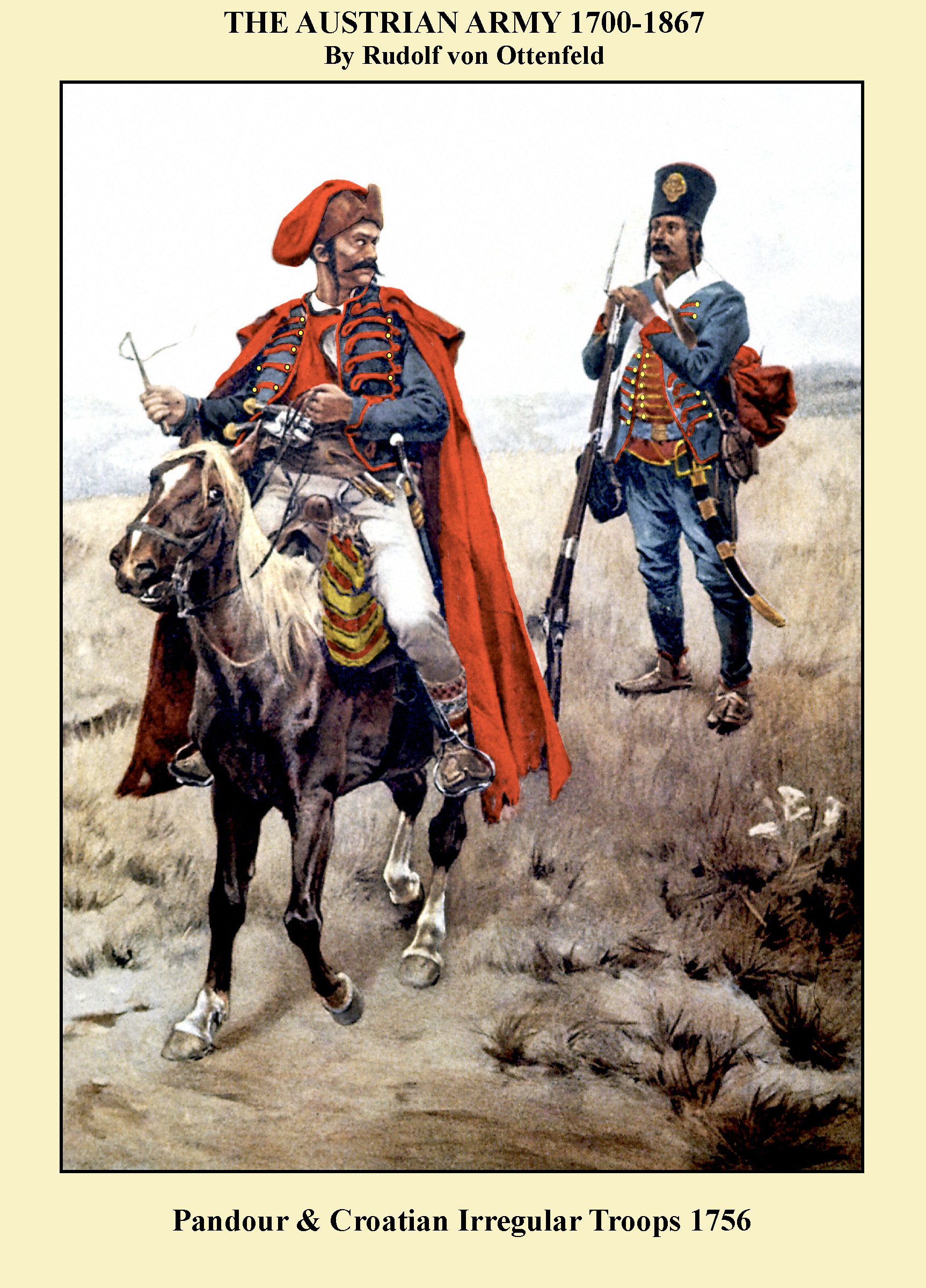

Irregular and Border Troops

The eastern edges of the Hapsburg lands bordering the Ottoman Empire, known as the Military Border were populated by tough and wild inhabitants, difficult to manage but expert in the type of warfare often described as “cut and run”. The very word ‘Pandour’ would strike fear into enemy soldier and civilian alike. The two figures shown here are typical of the time. The uniforms (such as they were) resembled the Hungarian type with the tight breeches and frogged jackets although cut much looser. A ubiquitous feature of all these troops was the red cloak with hood and they are often portrayed huddled round fires wrapped in these voluminous garments. The mounted figure shows a pandour of the Trenck Free Corps with his fur cap, not unlike a Hungarian Hussar, while the standing figure is a Croatian soldier from the Szluiner Border Regiment.